"Four novels in five years from her. That's amazing, and I'm so grateful for that quiet, calm, sane voice still being here."

Paul Magrs brought out his first novel in 1995. Last year he published his book on writing, The Novel Inside You. This year Snow Books are republishing his Brenda and Effie Mystery series of novels. He lives and writes in Manchester with Jeremy and Bernard Socks.

Easter Weekend, 2020

Paul Magrs brought out his first novel in 1995. Last year he published his book on writing, The Novel Inside You. This year Snow Books are republishing his Brenda and Effie Mystery series of novels. He lives and writes in Manchester with Jeremy and Bernard Socks.

Easter Weekend, 2020

Sometimes I think I’ve lived my whole life in lockdown. Many readers and writers I know secretly hanker to live like this. It must be why I’ve always been drawn to the novels of Anne Tyler, these past thirty years, since I discovered her. Tyler heroes tend to hanker for locked down lives, and they spend their days quietly aghast at the way everyone else goes flitting and changing about.

Up much of the night worrying and lying awake, fretting about Bernard Socks not being indoors, even though I know he's all right really. These are warm, moony nights for cats to go crazy in. At three I put on my slippers and take my keys to have a look at the bottom of the garden and of course, there he is, sleeping in the Beach House chair. I carry him indoors and he indulges me, running straight back out once I’m in bed.

This morning is beautiful. The sun so strong and the cherry blossom like great cumbersome sleeves on the branches outside my study window. The petals are starting to fly off already. There's just a few days of this.

Jeremy gets up saying, ‘It's like waking up each day and thinking that you've gone deaf. There's no city noise at all.’

A thousand people dead each and every day. Our rates are worse than anywhere in Europe. After us looking at Italy and Spain in horror for those weeks, it turns out those were the precise weeks our government should have been taking action, when they were simply telling us to wash our hands and to carry on as normal.

My treat to myself is the new Anne Tyler, which arrived the other day. It was on order for months. I take the parcel and open it and immediately wash my hands. Does cardboard carry the virus? Was the postman wearing gloves?

I've read her for thirty years and now she's writing characters slightly younger than me: characters who are already middle-aged, faded and disappointed. Characters who've missed out somehow. Taciturn, diffident characters who we meet on the very day that they try to catch hold of their lives again.

I always love her characters. They’re kind and they've usually lost out and, if it's through fault of their own, it's not a bad fault. Not usually. It's to do with a one-time hesitation, a fatal stepping back in order to let other, more pushy people dart forward. Her characters let others get on with being self-centred and ruthless and unkind.

Straight away I'm thinking of people who have leapfrogged their way onto and then over me in the past. It’s the same in Micah’s backstory here, when we learn a little from his college years. He stood by and let himself be robbed. There was a rich boy who simply took the patent for a software programme away from him. You’ve had comparable situations in the past, when you let people get away with stuff. And, like Micah, all you think you can do in these situations is pity the thief. Yes, I guess I might have been daft, letting them get away with it, but really… don't they have any ideas of their own? No talents? How desperate must they be to steal ideas, or to use up and exploit people and then move on past them?

I've been unlucky and foolish in the past. Hapless as an Anne Tyler character. I'm thinking of people I thought were friends and, looking back, realizing that there was always something smarmy about them. I look back at particular ones and think, Yes, the way they grinned was just like the Blue Meanie in the

Yellow Submarine cartoon and that should have been a danger sign.

At the moment I'm feeling sadder and more demoralised about my own work than I even realised. I took the week off to read and do very little work. I learned a bit more about painting with gouache and I gloried in 1970s Jackie Collins and that really was about it for me, this week. But I was also reading Anne Tyler and she put me into a kind of reflective, mopey mood. I love to read her but she makes me feel terrible, too, when I realise, like many of her characters, that I might have done my life wrong. I start to suspect I ought to have had harder edges, maybe… or fewer mixed feelings.

A tough day, feeling claustrophobic indoors. The only place I can sit is my study and that is wholly infused with the idea and atmosphere of work. I'd love to be able to spend the day in the garden. I think how lovely it used to be in the Beach House. I go out to take a look and the garden is so neglected. The Beach House is damaged and crammed with furniture we don't want and can't fit indoors. It's impossible to sit out here.

Jeremy started work in the garden, putting it all back together at the end of February. And I thought: maybe this year he'll sort it again. Then he found all those bones under the fallen tree at the far end and we had to get the police and CSI round, and that was a whole drama for a day. A ridiculous drama – soon resolved. (‘My money is on the remains of a badger,’ said the woman from CID.) The next day we visited my family in Trimdon and it was on the drive back we listened to the news and realised how close the pandemic was coming. We suddenly understood we were all going to be locked in for months, likely as not. So here we are.

Jeremy sits for two hours each day, transcribing the government broadcasts, decoding and fact-checking and commenting on them. Then he posts them online. The local groups are full of people he argues about politics with and they barely acknowledge the work he puts into this and other community initiatives.

I can hear the reasonable, doom-laden voice of the minister and the health experts playing through his laptop in the garden under my window. I want to tear out my hair. I did actually cut my own hair this morning. We’ll all be doing it before long.

I've been sleeping so badly. Lying awake worrying about Jeremy and our parents and Socks and everyone. Lying awake, too hot and thinking: a thousand dead every day. In hospitals I read that they have to turn everyone over and over again. It's best when they lie you face down: best for the lungs and the fluid on them. This image of passivity is horrifying in a way, so that everyone looks like giant babies, being turned over, helplessly.

Finishing the new Anne Tyler this morning, Easter Sunday. Jeremy and Socks have just got up and gone back into the garden. Reading and thinking, that's four novels in five years from her. That's amazing, and I'm so grateful for that quiet, calm, sane voice still being here. Telling us that it's okay to be wrong, imperfect, messy, timewasting… and it's never too late to go back and to make a change. Maybe.

And the theme of quietness! I just read a review of the new one on Amazon where someone says that when they give friends Tyler's books they complain about nothing happening! I think you might as well say that about your own life. (Well, perhaps some people do.) There's absolutely everything happening in her novels, I think. It's all there.

Oh, remember, when you wrote your little play about going to see your granda at the end of his life and you'd been chatting with a very famous producer friend and he said send it to so-and-so at such-and-such productions, his great supporter, all these years. Well, you had the assistant put onto you, of course, and you explained (modestly, stupidly) that perhaps the script was a bit quiet and a bit small scale for them. Then, of course, the assistant gave it a day or so before writing back, and telling you she found it a bit quiet and a bit small scale for them.

Oh well, it doesn't matter. Do you remember your first agent and how she used to say that you had to find something ‘high concept’ to hang all that ‘beautiful writing’ on, or else no one will care, because nothing really happens?

They only notice Anne Tyler now because they've been told to. All these years, and she's finally caught on. Thirty years ago I was lying in the park in Lancaster after my second year at University. That summer I read fifty novels in an empty house and wrote one of my own. I was living in lockdown back then, without even knowing it. All I did was read and write and venture out once a day to the park. Just the same as now.

And just like in an Anne Tyler novel, those thirty years went by and, though all the changes seemed very dramatic at the time, I’m doing all the same stuff as ever. I’m happy to, with the world around me in such constant disarray.

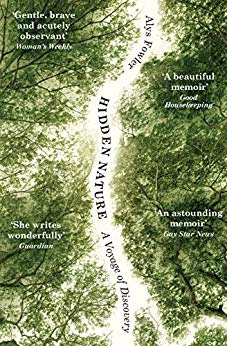

Redhead by the Side of the Road is published by Chatto and Windus