"It is the story of someone yearning for adventure, yearning for the feeling of being alive and active, but doing so within five miles of their own home."

Elen Caldecott is a writer for young people. She also teaches creative writing in university and community settings. Her latest book, The Short Knife, is an historical drama set during the collapse of the Roman Empire in Britain. It will be published in July 2020 by Andersen Press.

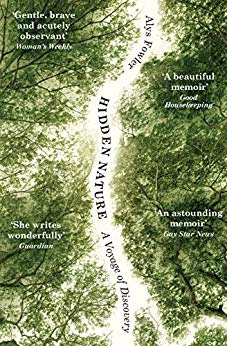

I had decided to write about Hidden Nature before Covid and our state of suspended animation

which came with it. But, on re-reading it for this blog, I was struck by its

relevance, especially as lockdown lifts and we take small steps towards

imagining what normal life might be.

Is this memoir, Alys Fowler writes of her decision to paddle

Birmingham’s canal-ways in an inflatable dinghy. She does this in small bursts,

over evenings and weekends, catching the bus, or cycling to the next stage of

the journey. It is the story of someone yearning for adventure, yearning for

the feeling of being alive and active, but doing so within five miles of their

own home. It is a memoir in which the plants and animals of the canals and

towpaths are companions and friends. They offer reassurance and familiarity to

Fowler at a time in her own life when she is coming to terms with her own

‘hidden nature’ as she questions, and finally acts upon, her own sexuality. She

emerges from her own state of suspended animation and she does so by meticulous

exploration of her own back yard.

I was initially drawn to the memoir as Birmingham is close

to my heart. I was an undergraduate there an eternity ago. Local lore had it

that Birmingham has more canals than Venice and, while I was a student, many of

the canals were undergoing gentrification, acquiring bars and restaurants where

there had formally been abandoned warehouses and small-scale industries.

Fowler, who many will know as a gardening writer for

broadsheet newspapers, took me on a tour of those familiar paths, but also gave

me an education. She is so knowledgeable about the plants and wildlife she

sees, and she shares this knowledge in the way friends might share gossip.

Buddleia, for example, gets its own few pages. It was, Fowler tells us, an

ornamental introduction to the UK that broke free of its garden confines after

the Second World War. The urban bomb-sites replicated the exposed limestone of

its natural habitat, and the slipstreams of railway embankments encouraged its

dispersal until it became ubiquitous. She passes so many of these common,

weed-ish, plants as she paddles her dinghy – first ineptly, later with a bit

more ept – and she has something wonderful to tell us about each one.

Meanwhile, in the background, her life is quietly imploding.

We hear about her husband, his long-term illness and the vicissitudes of caring

for him. We hear about the worry of work and moving to a new city. We hear

about a growing friendship with someone who will come to be crucial. But none

of these threads are the point of this book. Rather, the book shows rather than tells us how the natural world can help to make the Big Problems of

Life become a little smaller, a little more manageable.

There is a degree of tension in her descriptions of the

people she meets, as opposed to the non-human canal life. Many of the people

fishing, barbecuing, smoking, lollygagging about in the liminal spaces of the

city waterways, are drawn with a very broad brush. There are some assumptions

made about their lives, which aren’t really justified by the brief

conversations she reports having with them. But, when Fowler speaks about the joy, the peace and the

wisdom to be had by looking for small adventures, close to home, this book is

superb.

Hidden Nature is published by Hodder and Stoughton.

No comments:

Post a Comment