“It is a small peaceful hall, full of silence, glinting with textiles in deep earth-colours like a rusty rainbow, amethyst, chocolate, burgundy. White arches. A sheaf of open doors through which I see a patch of garden. Light filters down from high windows onto polished benches glimmering with embroidered cushions. On the left is a wood panel hung with taffeta of smoky topaz. Rose-brown silk lies lightly over a large book open on a lectern.”

The description is of the Etz Hayyim (‘Tree of Life’) synagogue in Chania, Crete, and it comes from Ruth Padel’s novel Daughters of the Labyrinth which was published in 2021. I visited the synagogue this year - a tiny building tucked away in a corner of the maze of streets and alleyways which were once the port’s Jewish quarter. An exhibition at the synagogue tells the story of the Jewish community, which had lived there for thousands of years, until the Nazis invaded. Rounded up and imprisoned, the Jews of Chania died when they were put onto a ship to be taken to the death camps. A British torpedo, fired in the belief that the ship was carrying munitions, killed them all. The synagogue was neglected and despoiled, but in later years restored, despite several arson attacks.

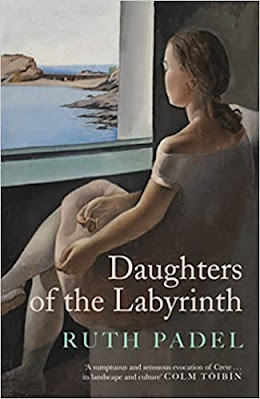

I found Daughters of the Labyrinth in the synagogue’s bookshop and spent the rest of our week in Crete reading it. Undoubtedly the effect of the book was enhanced by my surroundings – there is something very special about being able to compare a writer’s descriptions with the places around you. But I think the emotional impact of the story - which moved me to tears several times - and my admiration for the writing and the authenticity with which Padel writes would have been the same wherever in the world I was. And in fact the book begins and ends in the part of north London where I live, and right at the end Ri, the protagonist, visits the synagogue which I belong to. Ri is an artist, from Crete but living in London, recently widowed and adjusting to life alone. One of the many joys of the book is the way Padel thinks and writes about art, and the artist’s eye that Ri beings to her descriptions. She is planning a trip to India to paint, but a call comes from her family in Crete – her mother is ill. So she returns to Chania where her mother asks a question which changes everything she thought she knew about her family and her history. “Will you say kaddish for me?”

Kaddish is the prayer that Jewish mourners say for their loved ones (and indeed, in that tiny, restored synagogue in Chania, I said kaddish for my mother). But Ri’s mother, as far as she knows, is not Jewish. While her mother lies ill in the hospital Ri asks her father what on earth her mother means. And slowly a story unfolds – of heroism, tragedy and a girl who had to hide who she was, a Sara who became Sophia in order to survive and live with the huge trauma of being the lone survivor of her family and her community.

The pictures that Padel paints, of the lost Jewish community, the Cretan world around them, of Chania in the 1940s and now, of post Brexit Britain, of a world in the grip of Covid, all ring true. Padel’s deep knowledge of Greek mythology underpins the story and so does her 13 years of research. In an age of Holocaust fiction which is often sentimental and offers a false narrative of hope, this book gets it right again and again. Padel is better known as a poet and an academic, this is only her second novel. I will be seeking out her first, and also her poetry and non-fiction. If you are looking for a book which is satisfying on every level, I recommend Daughters of the Labyrinth.

Daughters of the Labyrinth is published by Corsair.

Below: the synagogue and streets of Chania. Photographs by Keren David.