"Writers Review usually concerns itself with the classier end of the literary spectrum but on this occasion I’m going to stride manfully into the murky world of the Rock biography ..."

Writers Review usually concerns itself with the classier end of the literary spectrum but on this occasion I’m going to stride manfully into the murky world of the Rock biography. And not just any rock biography – this last month a friend passed on a random wodge of them when he was having a clear out and it’s these I’ll be writing about as well as mentioning some others by way of comparison. This latest batch have been of variable quality, but good or bad it’s still been fascinating to read them.

Undoubtedly, some rock biogs are terrible. Radio presenter Danny Baker once dismissed David Bowie’s ex-wife Angie’s account of their life together, Backstage Passes, by saying you could open any page and read out any sentence and it would be dreadful. I did just that and came up with ‘Trying to have a relationship with a coke freak is like trying to eat an aircraft carrier.’ But notwithstanding, some rock biogs can be hands-down magnificent. Bob Geldof’s post Live-Aid effort Is that it? brilliantly portrays his early life in the cold-water chill of post-war Ireland and remains interesting when fame kicks in. John Cooper Clarke’s biog I wanna be yours offers the reader a magical picture of childhood in post-war Manchester and only goes off the rails once he becomes famous and, simultaneously, a heroin addict. Here, his unhappy tales of chasing his next fix become dull and repetitive.

But for now, let’s get back to this month’s batch:

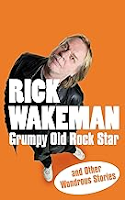

Rick Wakeman's music isn’t my thing but he seems like a genial soul so I've always warmed to him when I’ve seen him on the telly. His book generously credits his ghost writer – something that is not always the case in projects like these - and he quickly establishes his everybloke persona with chapter openers like ‘I love cars. I’ve had a few in my time…’. Alas, I found Grumpy Old Rock Star (Preface, 2009) hard work. On the printed page he comes over like a sozzled but harmless 'I'm mad, me' pub bore who might corner you at the bar. And, good God, his anecdotes are INTERMINABLE. His hearty pub-speak style does grate, and no cliché goes unused. Radio station switchboards ‘light up like a Christmas tree’ when swearing occurs on air, and Rick is living his life ‘on God’s green earth.’ Within are tales of Barry the Perv, Herr Schmitt and Tony ‘Greasy Wop’ Fernandez. Come on, Rick. It’s the 21st Century, not the ‘Hop off you Frogs’ 1980s.

Keith Emerson’s Pictures of an Exhibitionist (John Blake Publishing, 2004) is handicapped by the prog keyboard star’s clunky writing style. The book doesn’t credit a ghost writer but you would have thought his editor would have something to say about sentences like ‘From his casual shrug, could I be forgiven my suspicions that a game of deception was being played?’ It’s also rich in muso talk such as ‘By coincidence, Carl’s drum pattern happened to fit a left-handed ostinato figure I was working on…’ But before you know it he’s undermining his role as Prog’s own music professor by regaling us with tales of Emerson, Lake and Palmer sharing a roadside German prostitute.

For anyone who dislikes the prog-rock behemoths (as 1970s rock critics invariably described ELP) there’s plenty here to fuel their prejudice. ‘I’ve got this image of us creating a vast "sheet of sound" that defies conventional structures,’ writes Emerson. ‘There doesn’t appear to be one set time signature or a key structure but the total effect played by the three of us could be very prolific.’ Whimper fearfully and pray for the arrival of punk.

Lemmy’s White Line Fever (Simon and Schuster, 2002) is unexpectedly fascinating and he can certainly tell a tale. The Hawkwind and Motörhead bassist, who once said when asked for the secret of his success ‘Just keep going, like Attila the Hun’, is true to his word. Equipped with an iron constitution and an iron will, he burned through 40 years of Motörhead line-ups and died with his boots on a few short years after publication. You suspect, like The Alien, he had acid for blood. Despite his fearsome mien and even more fearsome consumption of amphetamine sulphate, he comes across as quite an old-fashioned and learned sort of chap. He even confesses that his greatest line in describing Motörhead to the world, ‘If we moved in next door your lawn would die,’ was actually nicked from American rock band The MC5. Unlike Rick Wakeman, Lemmy keeps his anecdotes short and to the point and is never less than entertaining. One former manager he describes as ‘a very interesting man… from an anthropological point of view. A complete ******* lunatic.’

Ginger Baker’s Hellraiser (John Blake, 2010) leaves you wondering how he lived so long. His parents’ generation would have called him a tearaway and he was undoubtedly mad, bad and dangerous to know. But among the tales of a decades-long smack habit, multiple infidelities and trying to set fellow band members hair on fire, you can’t help noticing that his daughter Nettie has done a really good job on the ghost writing.

And to finish, two biogs written by a band accomplice and a journalist respectively, rather than the musicians and their ghost writers. Richard Cole’s Stairway to Heaven (Pocket Books, 1997) and Stephen Davis’s Hammer of the Gods (Pan Books, 2005), both about Led Zeppelin.

The band’s oft told tale reads like a Greek tragedy and by way of comparison, I’d say the best account of them all is undoubtedly Barney Hoskyns’s Trampled Underfoot, where artfully chosen and often quite contractionary quotes illuminate this cautionary tale. (Jimmy Page claims his drug use never affected his playing. The rest of the world disagree.) As a rule of thumb you can tell how crappy a Led Zeppelin biog writer is by the ease and frequency in which they resort to aerial metaphors to describe the ‘flight’ and ‘crash landing’ of the Leds. Hoskyns doesn’t do this and his is a sad and sorry tale which also leaves you in awe of their extraordinary talents and multi-faceted music.

So, what of these two aforementioned accounts? Richard Cole, who was the band’s road manager throughout their 12-year existence, tells a weary tale, from the stale, obvious title onwards. His is a book of paint-peelingly sordid revelations, made even more distasteful by Cole’s corrosive misogyny. If you have pearls, prepare to clutch them. It’s like eavesdropping on the Russian Mafia drunkenly guffawing about how badly they treat the local prostitutes. On one occasion, for example, Cole persuades a gaggle of thirteen and fourteen year old girls to join the group on their private plane at Los Angeles airport. When the plane unexpectedly takes off for New York, the girls become distressed when they realise how much trouble they’re going to get into with their parents, who they probably told they were going to a sleepover with school friends. What larks.

The band’s oft told tale reads like a Greek tragedy and by way of comparison, I’d say the best account of them all is undoubtedly Barney Hoskyns’s Trampled Underfoot, where artfully chosen and often quite contractionary quotes illuminate this cautionary tale. (Jimmy Page claims his drug use never affected his playing. The rest of the world disagree.) As a rule of thumb you can tell how crappy a Led Zeppelin biog writer is by the ease and frequency in which they resort to aerial metaphors to describe the ‘flight’ and ‘crash landing’ of the Leds. Hoskyns doesn’t do this and his is a sad and sorry tale which also leaves you in awe of their extraordinary talents and multi-faceted music.

So, what of these two aforementioned accounts? Richard Cole, who was the band’s road manager throughout their 12-year existence, tells a weary tale, from the stale, obvious title onwards. His is a book of paint-peelingly sordid revelations, made even more distasteful by Cole’s corrosive misogyny. If you have pearls, prepare to clutch them. It’s like eavesdropping on the Russian Mafia drunkenly guffawing about how badly they treat the local prostitutes. On one occasion, for example, Cole persuades a gaggle of thirteen and fourteen year old girls to join the group on their private plane at Los Angeles airport. When the plane unexpectedly takes off for New York, the girls become distressed when they realise how much trouble they’re going to get into with their parents, who they probably told they were going to a sleepover with school friends. What larks.

Stephen Davis’s Hammer of the Gods is also a hair-raising expose of rock piggishness both within the group and their piratical road crew. Herein lurk tales of underage groupies, medieval brutality and Olympic-standard drug use.

But let's not end on such a negative note. Like Hoskyns, Davis loves the Leds. He even sings the praises of their underwhelming In Through the Out Door album, the last they made before their fearsome drummer, John ‘The Beast’ Bonham drank himself to death (48 vodkas, apparently…). Davis is an educated, erudite guide, quoting Primo Levi and snippets of Anglo-Saxon literature and while Cole’s book is a sordid swank along a very seedy avenue, Davis clearly revers his subjects, and finishes his book with a vivid and moving pilgrimage to John Bonham’s grave.