"Each character, real or imaginary, had their own quest and I accompanied them on their journeys though the uneasy England of 1824. And I like to think I helped them find their destinations and their fulfilment."

Dennis Hamley has been writing for an unconscionably long time. His first book was published in 1962. Since then he's written more books than he can count, including The War and Freddy, Hare’s Choice, Spirit of the Place, Out of the Mouths of Babes, the six novels in the sequence of medieval mysteries The Long Journey of Joslin de Lay, Ellen’s People and Divided Loyalties. He says: "It's wonderful to see my Coleridge project in print at last, and published by Fairlight Books, based in Oxford where I live. It came about when, after leaving hospital, I was visited by an ex-student of mine on the Oxford Creative Writing Diploma course - Louise Boland, a very good writer who had decided to set up as a small independent publisher specialising in literary fiction. That gave me the impetus to resurrect the project I'd been working on for years."

My interest in Samuel Taylor Coleridge merged into near-obsession at Cambridge, when my supervisor set our tutorial group an essay on STC’s theory of the imagination. This was in STC’s own college, Jesus. I loved this assignment, spent hours over it, found my understanding of literature changed utterly and received the supervisor’s comment ‘A noble effort’. Pleasing, but he omitted to say if it was actually any good. In 2002 a publisher, David Fickling, suggested I might write a novel about STC. So I did. It took me two years and he rejected it. And he was right. Incompetent and unreadable. So I got on with other things. But the resolve to write a proper novel about STC wouldn’t leave me. It took fifteen years for me to work out how to do it.

In 1972, a book called It’s a Don’s Life by Freddie Brittain, one-time fellow of Jesus (not to be confused with Mary Beard’s book) was published by Heinemann. Freddie mentioned a strange inscription in the first edition of Kubla Khan in the Old Library:

The writer of the above had much better have kept his sleeping thoughts to himself, for they are, if possible, worse than his waking ones.

It sounds damning. But perhaps it wasn’t. I needed someone to examine it closely. Who? A sizar, working as a library clerk, as had STC, perhaps?

My original failed novel depended on a what if? When in Sicily in 1804, Coleridge had a mysterious relationship with an opera singer, Anna-Cecilia Bertozzi. In 1808 he suddenly writes about her in his notebooks: ‘… her sincere vehemence of her attachment to me…Heaven forfend that I should call it Love.’

Back home, STC was in platonic love with Sara Hutchinson, the sister of Wordsworth’s wife, Mary. He called her ‘Asra’, to distinguish her from the other Saras, wife and daughter. And now, just in time, he sees ‘the heavenly vision’ of Asra’s face, ‘the guardian angel’ who saves him from the final temptation . I couldn’t resist thinking, ‘Yeah, right!’ What if STC had, unbeknown to him, left a son in Sicily and that son comes to England to find him?

So I had three main characters: one, STC, real; two fictional, George Scrivener, undergraduate who finds the Kubla inscription and works out its true significance, and Samuele Gambino, putative son in search of the truth. For George, an aspiring poet, the wish is that STC might be his mentor. Samuele needs to square his mother’s vision of genius with his teacher Mr Calvert’s of an opium-sodden wretch.

Perhaps the word ‘riff’ best describes what I was attempting. All facts would be accurate, but STC didn’t live by mere facts. We meet him with the line:

Samuel Taylor Coleridge had seen a ghost.

He was lodging with Dr Gilman and his wife on a sort of extended rehab. The ghost first appeares in Highgate High Street and then haunts him. Is this revenant the Second Person from Porlock? George Scrivener works out that there couldn’t even have been a first.

Mixing fictional and real characters is a risk worth taking. Samuele’s guide in his quest is Charles Lamb, who tells him who to visit and provides letters of introduction. So Samuele meetsTom Poole, STC’s friend in Nether Stowey, Wordsworth, Southey and, most important, STC’s brilliant daughter, Sara.

Once I had a structure in my mind, actually writing the book came relatively easily. Each character, real or imaginary, had their own quest and I accompanied them on their journeys though the uneasy England of 1824. And I like to think I helped them find their destinations and their fulfilment.

In 1972, a book called It’s a Don’s Life by Freddie Brittain, one-time fellow of Jesus (not to be confused with Mary Beard’s book) was published by Heinemann. Freddie mentioned a strange inscription in the first edition of Kubla Khan in the Old Library:

The writer of the above had much better have kept his sleeping thoughts to himself, for they are, if possible, worse than his waking ones.

It sounds damning. But perhaps it wasn’t. I needed someone to examine it closely. Who? A sizar, working as a library clerk, as had STC, perhaps?

My original failed novel depended on a what if? When in Sicily in 1804, Coleridge had a mysterious relationship with an opera singer, Anna-Cecilia Bertozzi. In 1808 he suddenly writes about her in his notebooks: ‘… her sincere vehemence of her attachment to me…Heaven forfend that I should call it Love.’

Back home, STC was in platonic love with Sara Hutchinson, the sister of Wordsworth’s wife, Mary. He called her ‘Asra’, to distinguish her from the other Saras, wife and daughter. And now, just in time, he sees ‘the heavenly vision’ of Asra’s face, ‘the guardian angel’ who saves him from the final temptation . I couldn’t resist thinking, ‘Yeah, right!’ What if STC had, unbeknown to him, left a son in Sicily and that son comes to England to find him?

So I had three main characters: one, STC, real; two fictional, George Scrivener, undergraduate who finds the Kubla inscription and works out its true significance, and Samuele Gambino, putative son in search of the truth. For George, an aspiring poet, the wish is that STC might be his mentor. Samuele needs to square his mother’s vision of genius with his teacher Mr Calvert’s of an opium-sodden wretch.

Perhaps the word ‘riff’ best describes what I was attempting. All facts would be accurate, but STC didn’t live by mere facts. We meet him with the line:

Samuel Taylor Coleridge had seen a ghost.

He was lodging with Dr Gilman and his wife on a sort of extended rehab. The ghost first appeares in Highgate High Street and then haunts him. Is this revenant the Second Person from Porlock? George Scrivener works out that there couldn’t even have been a first.

Mixing fictional and real characters is a risk worth taking. Samuele’s guide in his quest is Charles Lamb, who tells him who to visit and provides letters of introduction. So Samuele meetsTom Poole, STC’s friend in Nether Stowey, Wordsworth, Southey and, most important, STC’s brilliant daughter, Sara.

Once I had a structure in my mind, actually writing the book came relatively easily. Each character, real or imaginary, had their own quest and I accompanied them on their journeys though the uneasy England of 1824. And I like to think I helped them find their destinations and their fulfilment.

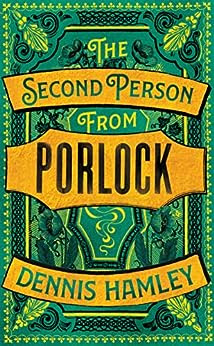

The Second Person from Porlock is published by Fairlight.

‘With no discernible sleight of hand this master storyteller, with effortless assurance and prodigious skill, weaves his mighty spell and conjures before our very eyes all we will ever need to know about the most famous lines of poetry that English ever produced.’ — Robert Lipscombe, author of The Salamander Tree and The English Project

‘With no discernible sleight of hand this master storyteller, with effortless assurance and prodigious skill, weaves his mighty spell and conjures before our very eyes all we will ever need to know about the most famous lines of poetry that English ever produced.’ — Robert Lipscombe, author of The Salamander Tree and The English Project

No comments:

Post a Comment